An Italian Wife Read online

Page 20

And after they were good and stoned, clumsy with it, thick and cloudy, the girls and boys had sex. Sort of. The rule was: try anything but. Stoned, and lying on the riverbank, the rocks hard beneath her back or legs or knees, looking into the stupidly grinning face of a boy, was the only time Penelope was happy.

Later, the girls told one another about the boys. They compared penis sizes and widths, techniques and lack of techniques, stupid things the boys said when they came. They imitated the sounds the boys made. Use similes! That was another rule: He sounded like a train slowing down, like a teakettle at full boil, like someone trying to go to the bathroom. His penis was like a Slim Jim, a bratwurst, a knitting needle.

They did this because everything was changing. Their parents were fucked-up—divorced, unhappy, even dead. There was a war that was never going to end. The government of the United States of America had betrayed them. They were lost. They were confused. They were searching for something that none of them could name. So they ran down to the river and gave boys blow jobs and got stoned and acted like nothing else mattered.

PENELOPE WATCHED HER mother step out of her ridiculous car—a pea-green Citroën. Her mother was, of course, an embarrassment with her fake British accent and Katherine Hepburn pants and that car. Not as bad as Rainier’s mother; she wore jeans and Army jackets, said fuck all the time, got stoned. Every spring, they showed up, all the mothers, for St. Lucy’s Mother’s Day Tea. It was a misnomer, this tea. There was a full bar where Penelope’s mother got an endless supply of gin and tonics. Mrs. Landon gave a slide show of the girls looking studious, waving field hockey sticks, performing in plays, or making pottery. The freshmen had to serve everyone else, a lavish five-course dinner on china and linens, with crystal and silver.

Rainier showed up in Penelope’s doorway. She opened her palm to reveal a joint.

“I need it to get through this,” she said. “What do you say?”

Penelope’s mother had paused to talk with Samantha’s mother. Samantha’s mother was an artist, with unruly curls and flowing dresses.

Quickly, Penelope pulled Rainier inside, closed the door, rolled up her still-damp bath towel, and stuck it under the door. Rainier had already lit up, and that sweet, sharp, beautiful smell filled the room. While Rainier took a hit, Penelope closed her eyes and took a deep breath.

“Not the best,” Rainier said, “but it’ll take the edge off.”

The girls passed the joint back and forth until they heard high heels in the hallway. Mothers were arriving. Penelope had a nice buzz going.

“Thanks,” she told her friend.

Rainier hesitated at the door.

“What?” Penelope said.

“My mother said she’s going to bring me some acid. She’s been doing a lot of it out at her house in Nantucket. She says she thinks it’ll do me good.”

Penelope shook her head as if it would help her understand better. “LSD?” she managed finally.

Now voices, high and shrill, filled the corridor outside the room.

“Maybe next time we go down to the river we can all do it?” Rainier said, uncertainly.

Penelope didn’t want to seem afraid, although she was. A boy from Maxwell Academy had taken LSD in the fall and jumped off the chapel roof, believing he could fly.

“That boy who died was stupid,” Rainier said. “You never drop acid alone.”

“I even forgot about him,” Penelope lied.

There was a loud knock on the door, and her mother’s stupid voice: “Penny?”

Penelope rolled her eyes. “She knows I hate that name,” she said, and yanked the door opened.

Her mother and Mrs. Woodson were standing there. Penelope saw her mother’s nose twitch and cursed herself for not opening the window.

“Smells sour in here,” Mrs. Woodson said, walking right in and cranking the bank of windows open. “Don’t you girls ever clean?” She had stiff beauty-parlor hair and orange ovals for fingernails.

“Deborah stepped out for a minute,” Penelope said.

Then she giggled. Deborah Woodson had gone into town to a doctor; she thought she might be pregnant. Deborah had not followed the rules. She had done everything, including. She had done it with Jeremy Jackson, whose father was a mucky-muck in the Army, West Point, this and that, now dead.

Her mother looked at her sharply.

“I thought she’d be back by now,” Penelope said, strangling another giggle.

“I saw your mother in the parking lot, Rainier,” Mrs. Woodson said. “Isn’t she exotic? What do you call those shoes she has on?”

“Dr. Scholl’s,” Rainier said.

“I told Deborah I would escort you to the dining hall if she wasn’t back when you came,” Penelope said. It was all so stupid and funny, this tea and Mrs. Woodson in her Chanel suit and her own mother frowning at her. Penelope sat on her bed with its pale-yellow duvet and Marimekko sheets, and hid her face in her hands, laughing.

“Well, I don’t understand,” Mrs. Woodson said.

Rainier started to laugh too.

“Honestly,” Penelope’s mother said. She took her by the arm, roughly, and yanked on her.

Penelope used to dismember her dolls. She loved the way the arms and legs pulled out of the sockets, the way the heads came off with a pop. It seemed her mother was trying to take her apart, the way she pulled on her. Or was that just the pot making her feel all loose and liquidy?

She looked up at her mother, and for an instant Penelope felt bad for her, for all the mothers who paid so much money to send their daughters to a fancy school to learn about sex and drugs.

“I’m sorry,” she managed to say.

She got to her feet clumsily. She straightened her shoulders, her head feeling slightly disconnected from the rest of her body.

“Shall we?” she said.

Her mother, that Anglophile, would like that. Penelope glanced over at her, and yes, she was smiling.

AFTER THE DINNER, bloody roast beef although half the girls and even some of the mothers were vegetarians, Penelope leaned against her mother’s car. The sky was purple and black. Her head hurt a little and the taste of the coconut layer cake was making her queasy.

“Well,” her mother said, not looking at Penelope, “I have a good lead. I’m driving to Rhode Island tomorrow.”

“Three hours and seventeen minutes,” Penelope muttered. She had timed how long it would take her mother to bring up yet another lead on the Holy Grail of finding her birth mother.

“What?” her mother said. Her face had gone blank, the way it did when she drank too much. Her eyelids drooped in a way that half an hour ago might have been sexy but now looked kind of sad.

She had been adopted by a rich family in Vermont as a baby, but all of a sudden all she could think of was who her real parents were. Every few weeks, she went off somewhere, chasing some wrong information. At Easter, she’d flown to Colorado, only to learn that the couple who might be her parents had had a boy. It was all so stupid, so long ago. If Penelope’s mother had given her away at birth, Penelope doubted she’d be wasting her middle age looking for her. She’d say, Fuck you very much for abandoning me and move on with her life.

Her mother was telling her about Rhode Island, a Catholic hospital.

“This time I think I’ve found her for real, Pen, Penny, my Penelope,” she said drunkenly. Her mother had lived in England for a year or something a long time ago, and she used this fake accent that drove Penelope crazy. When she drank too much, her fake English accent got even stronger.

Penelope’s leg jumped, up and down, up and down. She wished she’d taken the end of that joint with her so she could sneak into the ladies’ room and have a hit or two, just to calm her down. Just to blot out her mother’s voice.

Across the parking lot, Penelope watched Rainier and her mother bent together at their Volvo. Her stomach flipped over. Rainier was probably getting the LSD right now, and tonight or tomorrow night Penelope was going to have

to take it. She sighed. Why did everything have to get complicated?

“I was thinking you could come with me,” her mother was saying. “We could have a nice drive in the morning after breakfast and check out this lead.”

Penelope chewed her lip. Rainier came skipping across the parking lot. As she passed them, she flashed a peace sign. Or maybe a V for Victory?

“I don’t like that girl,” her mother said in a low voice. “She always looks like she’s up to no good.”

“She’s all right,” Penelope said.

She was thinking of that boy again, the one who jumped out that window, and her stomach cramped. She remembered how Rainier had said after they heard, “God! I wonder if I blew him? I hope so. You know, it would be a pity to die without ever doing anything like that.” Penelope had had the same thought, but it had made her sick to think it. Not Rainier. Rainier had laughed.

“So,” her mother said, jingling her keys, impatient to leave, “what do you say?”

Maybe Rainier would wait until tomorrow and if Penelope wasn’t here, or got back super late, she could avoid this whole LSD thing. But a whole day, in the car, with her mother. Which was worse?

“Stop jiggling your leg, Penelope,” her mother said, grabbing Penelope’s knee and holding on tight. Beneath her mother’s hand, Penelope’s leg trembled, wanting to move.

“Stop,” her mother said again. Penelope saw that she had a faint smear of lipstick across her two front teeth. Had it been there this whole time?

Rainier had gone inside now and was miming something to Penelope, something too complicated to mime. It could be: Let’s go smoke a joint. It could be: Let’s go give some lucky boys a blow job they’ll never forget. It could be: Let’s drop this acid now! Penelope turned her gaze away from Rainier. She felt suddenly very tired.

“Sure,” Penelope told her mother.

“Really?” her mother said, so pathetically pleased that Penelope wished she had said no. “That’s great, darling. Shall we have breakfast first?”

Penelope shrugged. “I guess,” she said.

Her mother kissed her on the cheek, her breath all coconutty and sour gin. “All right then,” she said. “Cheeri-o until morning.”

Penelope slipped away from the hug her mother was drunkenly trying to execute. “Cheeri-o!” she muttered heading up the hill toward Figg. “Ta-ta and all that bloody rubbish!”

JULIE WAS STANDING in the hallway outside the common room when Penelope walked in. Last year, Julie had been Ms. Matthews; this year she said to call her Julie. She taught English and coached the debate team, a dismal group that always came in last place. But Penelope liked the way Julie wore her hair cut short and shirts she embroidered herself, and an old pair of jeans with a red felt heart sewn on the butt.

“You okay?” Julie asked, frowning. Her hair was rust-colored, and so were her eyebrows and her freckles, which made her look a bit disconcerting.

“You know.” Penelope shrugged. “Mothers.”

And LSD trips, she added to herself. And flying out windows. And death. She forced a grin but it came out more like a grimace.

“Ah!” Julie said. She cocked her head toward the door to her suite. “Want to sit and talk a bit?”

Relieved, Penelope nodded and followed her inside. The red heart on the back of her jeans seemed to smile at her. Penelope loved Julie’s suite, even though she wasn’t one of the girls who visited here often. Last year, Pamela Grundy had practically lived in here. This year, August Frank could almost always be found here. There were rumors about them, Pamela and now August, that they were lesbians. And so was Julie. But Penelope thought it was dumb to think every woman with short hair was a dyke.

The suite was small, just two rooms. The bedroom lay behind a closed door; the sitting room and kitchen were separated by a counter with two stools at it. According to August, Julie had salvaged those stools from an old diner in Worcester. The seats were aqua vinyl. And Julie’s plates and bowls were all pink and orange and baby-blue, also rescued from somewhere. That’s what she does, August said. She rescues things. August never went down to the river, giving more evidence to her rumored lesbianism.

“So,” Julie said, “mothers.”

She took out two metal cups, one green and one gold, opened a jug of red wine, and poured some in each glass. “Don’t tell,” Julie said, winking. “At Rosemary we relied on our house mother to buy all of our alcohol.”

Penelope pretended not to be surprised. The wine tasted like grape juice.

“Of course,” Julie said, “we liked vodka and orange juice. What is that called? A screwdriver, I think? We carried it around and no one knew the difference.” She smiled to herself.

“My mother’s on a quest,” Penelope said. “She wants to find her real mother. Like, what’s a real mother anyway? She was adopted,” she added.

“So was I,” Julie said. “But I don’t want to meet the woman who gave me away. I mean, honestly. Fuck her. Right?”

Penelope sipped her wine. It was like Julie wanted to shock her. Suddenly, Penelope wanted to be in her own room listening to her new Cat Stevens album. But Julie was pouring them each more wine.

“Tell me,” Julie said, “what do you girls do down at the river?”

When Penelope choked on the wine, Julie laughed. “Don’t worry. I won’t tell. Is it drinking?”

Penelope shook her head. She loved that song, “Wild World,” and she wanted to play it over and over until it became part of her. That’s what she did when she liked a song.

“Pot, then?” Julie asked.

“I . . . I don’t know,” Penelope said, and Julie laughed again.

“I never liked it myself, but hey,” Julie said. “And I suppose Maxwell boys are there too.”

The album was called Tea for the Tillerman. Penelope wondered what a tillerman was. Julie probably knew. Julie had been the one to tell her who Penelope was in Greek mythology, a woman who waited for, like, twenty years for a man to return for her. She just sat there knitting or something. Leave it to her mother to give her such a stupid name.

“Just be careful,” Julie was saying.

Penelope stood up, lightheaded from the two glasses of wine.

“Don’t want anyone coming down to tell me they’re preggers,” Julie said.

Deborah’s face came to Penelope’s mind. At the tea, she had looked over at Penelope solemnly and ran her finger across her throat. Preggers.

“Well,” Penelope said, “thanks for the talk and stuff.”

Julie touched her arm so lightly it felt like a feather had landed there. “Do you like the boys?” she asked. “Do you like kissing them?”

Her fingers stayed there, hardly touching. Penelope thought of butterflies, light things. “I guess so,” she said.

“At Rosemary we kissed each other,” Julie said. “To practice, you know. We didn’t mean anything by it. We weren’t dykes or anything. No, it was more like the Native Americans. When a boy came of age, his mother taught him what to do. How to please a woman.”

“Really?” Penelope said. She felt confused, and a little drunk. Julie’s fingertips seemed suddenly burning hot.

Penelope was tall, one of the tallest girls at St. Lucy’s. And Julie was small. A slip of a thing, Penelope’s mother had said when she’d met her last fall. Julie stood now on tiptoe, and tilted her face upward, like a girl waiting to be kissed. Without hesitating—and that was what confused Penelope even more later—Penelope leaned down and kissed her, full on the mouth. She had never been anywhere so soft. She thought she might crawl into those lips forever. Use similes! She told herself. Like clouds. Like marshmallows. She heard herself gasp a little, at the softness. She couldn’t stop pressing her lips against Julie’s. All those Maxwell boys with their rough faces, their chapped lips, their boy tastes. Julie tasted like grapes. Like cotton candy. Now their lips parted and their tongues were touching, Julie’s soft like . . . like what? Penelope couldn’t think. She felt herself getting w

et down there where Maxwell boys jammed their fingers in.

Then like an interrupted dream, Julie pulled away. “Remember that,” she said, her mouth wet with their spit, “when you’re kissing that Maxwell boy tonight. See?”

Penelope nodded stupidly and stumbled out of Julie’s suite. Some girls were sitting cross-legged in the common room and looked at her all funny.

“Did you hear?” one of them said. “Deborah Woodson slit her wrists. They’ve taken her to the hospital.”

“What?” Penelope said. She thought of Deborah dragging her finger across her throat.

“Don’t worry,” that little tight-ass Yvonne Mack said. “She did it in the library. Not in your room.”

Just then Julie’s door flew open. She had on the faded corduroy jacket she always wore, and a panicked look. Penelope ran to her. Julie grabbed her by the wrist, dragging her along.

THE GIRLS STILL RAN down the hill to meet the boys, even with Deborah in the ER and then up in the psych ward. They went down there and got stoned and took off their panties and let the boys finger them. They opened their mouths and the boys stuck their dicks in, pushing against their teeth, yanking on their hair. Don’t swallow! That was one of the rules. But Penelope always did. She’d read somewhere, maybe in Cosmopolitan magazine, that semen was a good source of protein. But that wasn’t why she did it. She did it because she earned it. All that work, her jaw sore for hours afterward. It didn’t taste bad either. Like saltwater. Like asparagus. Like the smell in chemistry lab.

But tonight, after Penelope and Julie got back to St. Lucy’s from the hospital, the calls made to Deborah’s parents to come first thing in the morning, Deborah locked up in the psych ward, Julie unlocked the door to Figg and said, “Boy, do I need a drink. You?”

Kitchen Yarns

Kitchen Yarns Waiting to Vanish

Waiting to Vanish Morningstar

Morningstar Something Blue

Something Blue Providence Noir

Providence Noir Somewhere Off the Coast of Maine

Somewhere Off the Coast of Maine Jewel of the East

Jewel of the East Queen Liliuokalani: Royal Prisoner

Queen Liliuokalani: Royal Prisoner The Knitting Circle

The Knitting Circle Leonardo da Vinci: Renaissance Master

Leonardo da Vinci: Renaissance Master An Ornithologist's Guide to Life

An Ornithologist's Guide to Life The Red Thread

The Red Thread She Loves You (Yeah, Yeah, Yeah)

She Loves You (Yeah, Yeah, Yeah) Brave Warrior

Brave Warrior How I Saved My Father's Life (and Ruined Everything Else)

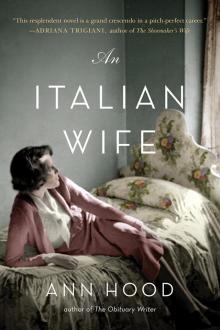

How I Saved My Father's Life (and Ruined Everything Else) An Italian Wife

An Italian Wife Anastasia Romanov: The Last Grand Duchess #10

Anastasia Romanov: The Last Grand Duchess #10 Prince of Air

Prince of Air Amelia Earhart: Lady Lindy

Amelia Earhart: Lady Lindy Places to Stay the Night

Places to Stay the Night Little Lion

Little Lion Comfort

Comfort Angel of the Battlefield

Angel of the Battlefield